The Streisand Threshold: Choosing one’s battles

There is a tremendous amount of pseudoscience and other misinformation that circulates– seemingly unimpeded– on the internet. Consequently, it can be a daunting task for those of us who fight against it to know which targets are an effective use of our time and effort. There are various considerations that might inform one’s decision about where (or toward whom) to direct one’s science advocacy or skeptical outreach:

One’s level of personal interest and aptitude in a topic usually plays a big role in that decision. Responsible bloggers or podcasters will generally refrain from expounding confidently on topics about which they lack sufficient background knowledge to give a fair and accurate account of the state of the field.

It may depend in part on whether the blogosphere already appears saturated with articles about a particular topic. That’s not to say that there’s anything inherently wrong with doing one’s own take on a topic that many others have written about, per se. Even if one has nothing new to bring to the topic, it can still be good practice, and allows for some insight into the standard of quality set by other writers, and what it takes to match that. Sometimes something as simple as a different presentation style or a different audience can get the message through in a novel manner. However, one might prefer to find under-filled niches over re-inventing the wheel.

It may also depend in part on the extent to which one perceives the myth (and/or its proponent) to be dangerous. That’s something that depends partly on the content of the message one is considering countering, how prevalent it is, and the harm that could be caused if the public accepted the misinformation as fact.

The Streisand Effect

For cases in which a myth or charlatan has not yet achieved any substantial reach, we must consider whether or not shining the light of science and reason on it might backfire by exposing it to a larger audience than it previously had.

This phenomenon is known as the Streisand effect. It is named as such due to an incident a few years ago in which photos of the house of famous singer, Barbara Streisand, were leaked to the internet. Streisand demanded the pictures be taken down, which ended up publicizing their existence to a far greater extent than would likely have been the case had she said nothing at all.

Her case is far from the only one in which an attempt to repress something backfired spectacularly.

An unflattering Super Bowl Halftime show pic that Beyonce’s publicist wanted removed from the web.

With this in mind, it’s reasonable to wonder how likely it is that debunkers might unintentionally boost the popularity of the claims they are countering (and/or their proponents) by the act of publicly refuting them.

The Converse of the Streisand Effect

On the other hand, there have also been instances in which popular misconceptions were essentially ignored by experts in hopes that they’d fade into obscurity, which then resulted in specious ideas gradually gaining more and more momentum. This is essentially what happened with the rise of the anti-GMO movement. Many scientists figured that as more and more research results were published, that the evidence would speak for itself, and those preliminary fears would eventually be alleviated. Instead, the anti-GMO movement just kept growing until there emerged an enormous gap between science and public perception on the topic of genetically engineered food safety, (larger than for any other publicly controversial scientific topic, according to PEW reports). It wasn’t until the anti-GMO movement had a good 15-year head start (give or take) and a well-established disinformation campaign on the internet that an appreciable number of scientists and science advocates really started to fight back. Some of the myths had already become so firmly cemented in people’s minds that replacing them with more accurate information has been an uphill battle. Certain talking points seem to be recycled perpetually, regardless of how many times they’ve been debunked, thus making science outreach feel to many like a Sisyphean task.

Whether or not you (the reader) like Genetically Engineered crops is not relevant to the central point of this section, but for anyone interested, I’ve taken on many of the aforementioned myths here, here, here, here, here, here, here, here, here, and here.

Rather, the point is that there existed (and still exists) a huge gap between science and public perception on the topic of Genetically Engineered foods, and ignoring it didn’t make it go away. It’s hard to say what might or might not have happened if there had been a greater push-back against the rising anti-GMO movement in the 90s and early 2000s, but it’s clear that ignoring it didn’t help. This is just one example, but it shows that there exists a flip side to the Streisand effect, and that it should therefore not always be a deterrent to countering misinformation.

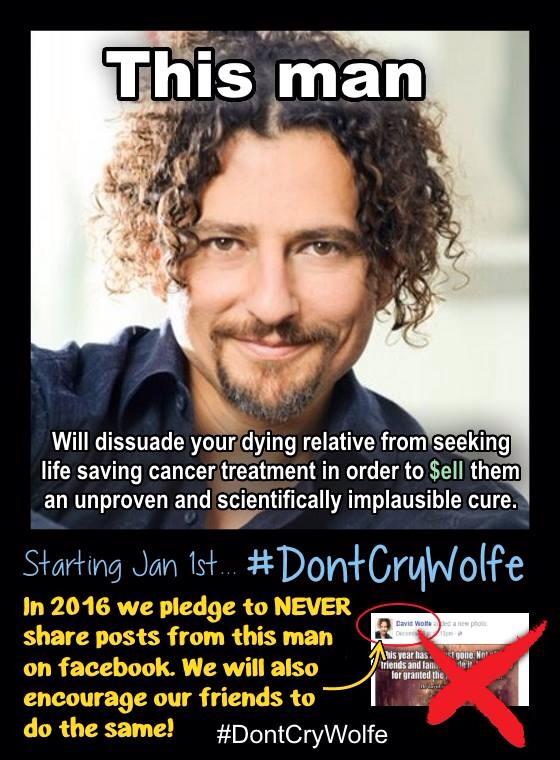

Don’t Cry Wolfe

In late 2015 through 2016, many public figures involved in science outreach (myself included) ran a campaign called Don’t Cry Wolfe. Its purpose was to expose the dangerous misinformation of an inexplicably popular public figure by the name of David “Avocado” Wolfe, and encourage people not to share his posts or boost his reach which, even at that time, was already considerable. During the campaign, I recall some commenters on my FB page raising the question of whether the adage that “any publicity is good publicity” applied here. Without knowing what it was called, they were expressing concern that the campaign might result in the Streisand effect. Due to insufficient data, it’s difficult to determine what the net result of the Don’t Cry Wolfe campaign truly was, but there were no superficially obvious signs that it backfired.

Image from the #DontCryWolfe campaign.

Don’t Cry Wolfe was also an interesting case in that Wolfe’s style of roping in followers with seemingly innocuous posts and then hitting them over the head with pseudoscience had created a situation in which even people who would normally avoid dangerous woo were following Wolfe’s page and sharing his (less batshit crazy) posts, thus unwittingly increasing his audience and reach even more. Consequently, a lot of people in the online skeptics’ community who simply hadn’t noticed what Wolfe was all about immediately unfollowed him once they caught wind of the Don’t Cry Wolfe campaign.

More importantly, although there were probably multiple reasons it didn’t backfire spectacularly, I suspect the main reason was because he already had nearly 6 million followers at the time, whereas most participants in the campaign had only on the order of tens to hundreds of thousands. There was no keeping the proverbial cat in the bag (Wolfe in the bag?) by ignoring him at that point. Despite the number of science advocates involved, it was just not realistic that we would unwittingly lure in more new Wolfe fans than we dissuaded, especially given the skeptical disposition of our audiences. We knew ignoring him wouldn’t work, and we had nothing to lose by trying.

The Streisand Threshold

We’ve seen examples of both the Streisand effect and its converse at different ends of the spectrum. This raises the question of whether there exists a threshold somewhere between the extremes representing a demarcation between cases in which the Streisand effect does or doesn’t apply. Although I can’t say for certain, I suspect there probably does exist such a threshold, even if the boundary is fuzzy.

Based on the above examples, I would guess that it depends largely on the discrepancies in the reach of the exposure and the exposed. Barbara Streisand and Beyonce Knowles are extremely famous individuals, so when they or their publicists attempt to take down some unflattering picture or piece of information, it draws massive public attention. On the other hand, someone like David Avocado Wolfe was already reaching so many people that there was no real risk in some medium sized science pages calling him out publicly, and there was no chance in hell he was going to just wither away and disappear by continuing to ignore him.

The Tale of Nutritarian Nancy, PhD, BS, WTF (or whatever)

In 2015, there was a small FB page run by a “holistic practitioner” who called herself Nutritarian Nancy, PhD, who had apparently acquired some fluff degree from some online holistic nutrition degree mill, and who was making a lot of bogus fear mongering health claims. Imagine a less successful version of Vani Hari (the Food Babe).

Some science advocates didn’t appreciate her spreading misinformation, and resented her propping herself up with what they took to be illegitimate accolades. So, they shared her posts in groups and would swarm her comments sections, sometimes with reasoned rebuttals and sometimes (unfortunately) with plain old angry rants. I recall being concerned that bombarding her page might boost her reach and render her much more dangerous than her little page ever could have become without that engagement boost.

But it never happened. She eventually changed her page’s name to Natural Nancy, and skeptics and science advocates basically just grew bored with her and stopped paying attention to her. I’m told she eventually changed her page name again after that, but her following never exceeded about 4,500 followers or so. Considering how easy it is to lure people in with pseudoscience (compared to skepticism and science advocacy), it’s fair to consider her efforts a failure for pseudoscience and fear mongering, and a win for science and skepticism.

The Take Home Message

I think the bottom line here is that the Streisand effect isn’t a major problem for participants in anti-pseudoscience outreach unless the reach of the debunker is significantly greater than the reach of the idea and/or person being debunked. We should nevertheless be cautious in borderline cases, because we’ve seen the Streisand effect in action, and we don’t currently know the exact popularity ratios at which it might occur. There may also be other relevant variables we are not aware of, or that are less easily measured. This will necessarily involve some guesswork with borderline cases, but we know that there can be consequences to letting a misinformation vector grow too big before pushing back.