A popular theme among movements which oppose certain aspects of modern science and technology is the notion that people were healthier in the “good old days,” back before the introduction of many modern scientific advancements. The idea is that there was once a time when there were no artificial chemicals, no fluoridated water, no genetically engineered crops, no vaccines or other modern medical science, all food was organic, and everyone led longer, happier, and healthier lives. There are many variations of this particular worldview aesthetic, and different ones have different ideas as to what the biggest alleged culprits are. Some hypothesize various conspiracies involving governments and/or corporations, whereas others may simply view new technology as “unnatural” (ergo undesirable) in their estimation. The common thread, however, is the belief that people are worse off now than in centuries past, and that one or more forms of human intervention are at fault.

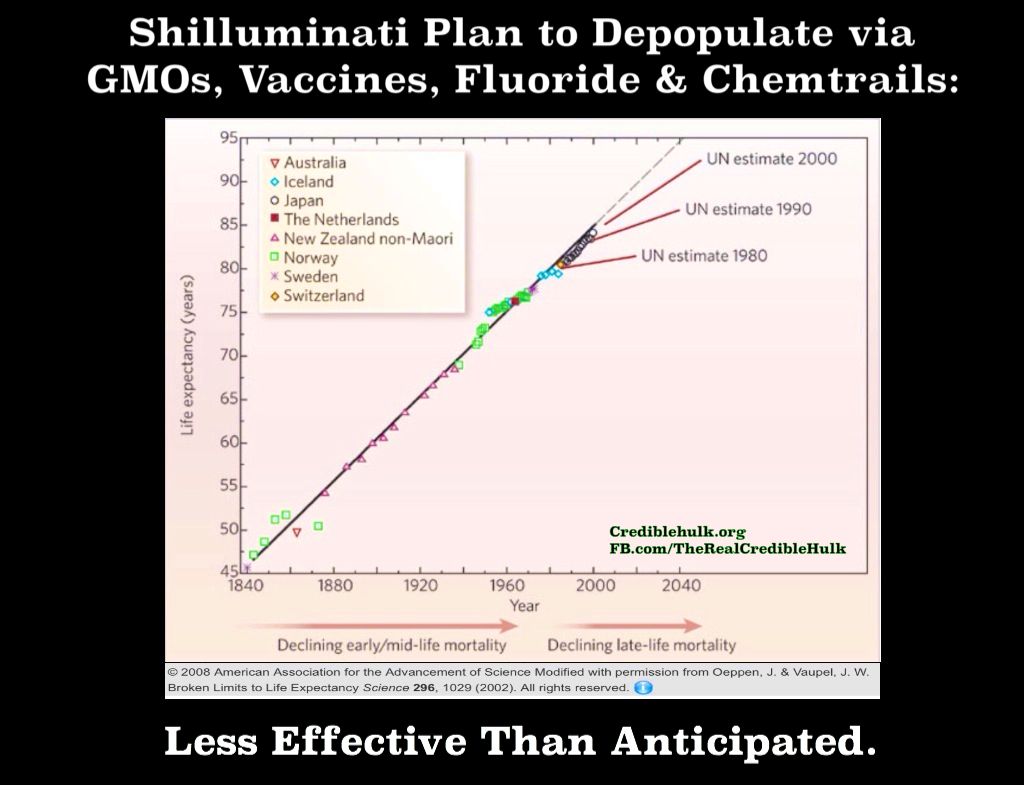

One of the most obvious things one might think to bring up when presented with this sort of historical revisionism is the fact that life expectancy has steadily increased in nearly every country on the planet over the last 150-200 years or so.

Child Mortality

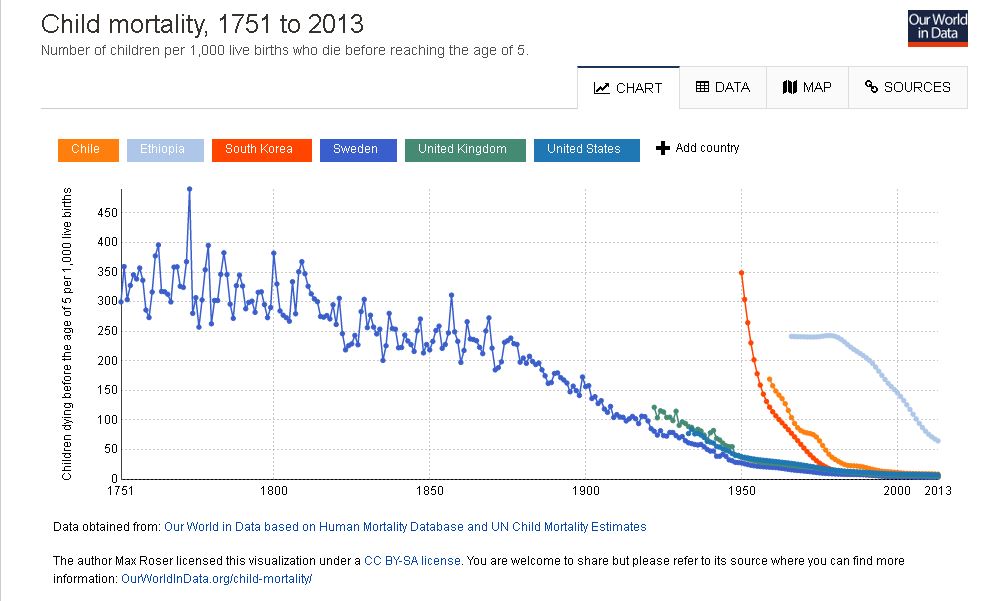

In response, some people will attribute the rise in life expectancy solely (or at least primarily) to a decrease in child mortality. There is some truth to this. As we can see from the graph below, child mortality has indeed decreased dramatically in the past 250 years or so. It also makes sense that changes child mortality rates would obfuscate the interpretation of data indicating an increase in life expectancy.

However, putting aside the fact that a decrease in child mortality rates is one the ways in which the advancement of scientific knowledge has benefited people, the idea that that it is sufficient to account for the increase in life expectancy is a myth. I think this is worth addressing because even a lot of skeptics make this argument.

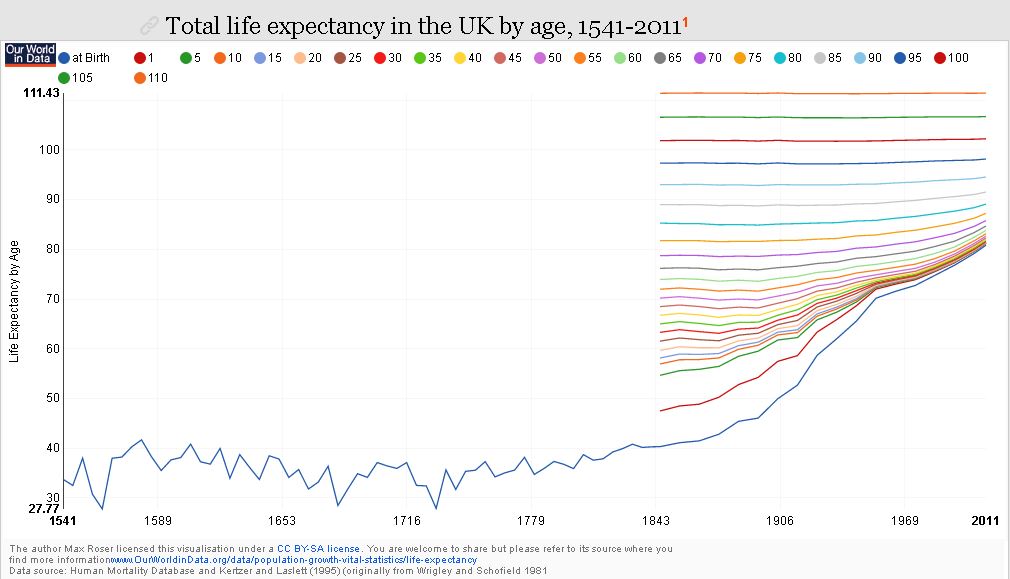

Although it’s true that child mortality can skew mean life expectancy results, it should come as no surprise that statisticians know this and take it into account. It turns out that life expectancy is still much higher today (particularly in developed countries) than in the past even when adjusted to compensate for the effects of high child mortality rates. This is relatively easy to do when comparing data from populations in recent centuries, simply because people wrote it down. For example, rather than computing life expectancy from birth, which assigns a lot of weight to the effects of child mortality by default, statisticians use “life expectancy at age x.” Child mortality is defined as the number of children dying before their 5th birthday. For example, this chart of life expectancy over time in the UK gives the numbers over time for several different values of “x.”

Click here to see the interactive version

Lo and behold! It turns out that expectancy is on the rise even if adjusted for the decrease in child mortality.

“To see how life expectancy has improved without taking child mortality into account we therefore have to look at the prospects of a child who just survived their 5th birthday: In 1845 a 5-year old had a expectancy to live 55 years. Today a 5-year old can expect to live 82 years. An increase of 27 years.”

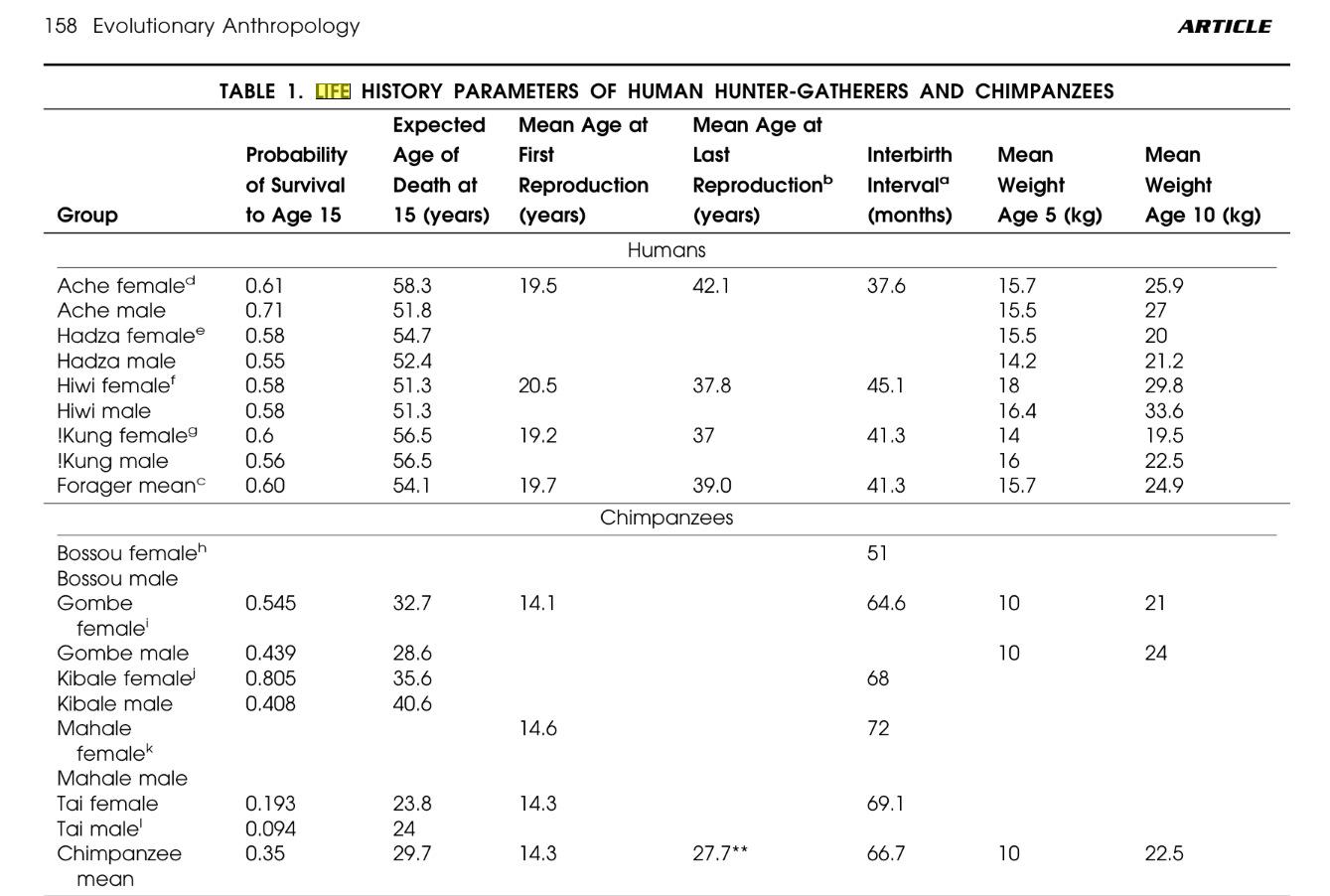

Hunter Gatherer Times

That said, in the case of Paleolithic hunter-gatherers, the data is not as straight forward to obtain. This is simply because paleoanthropologists have to apply specialized techniques to determine the age at which a specimen died, and because we’re forced to rely on the tacit assumption that the limited number of specimens available to us constitute a representative sample. These researchers included “life expectancy at age 15.” Granted, the mean life expectancy is greater than 30 (lower to upper-mid 50s is most common), compensating for people dying before age 15 does not come even close to putting the mean life expectancy in the ranges we see today (typically 70s and 80s depending on which countries one looks at).

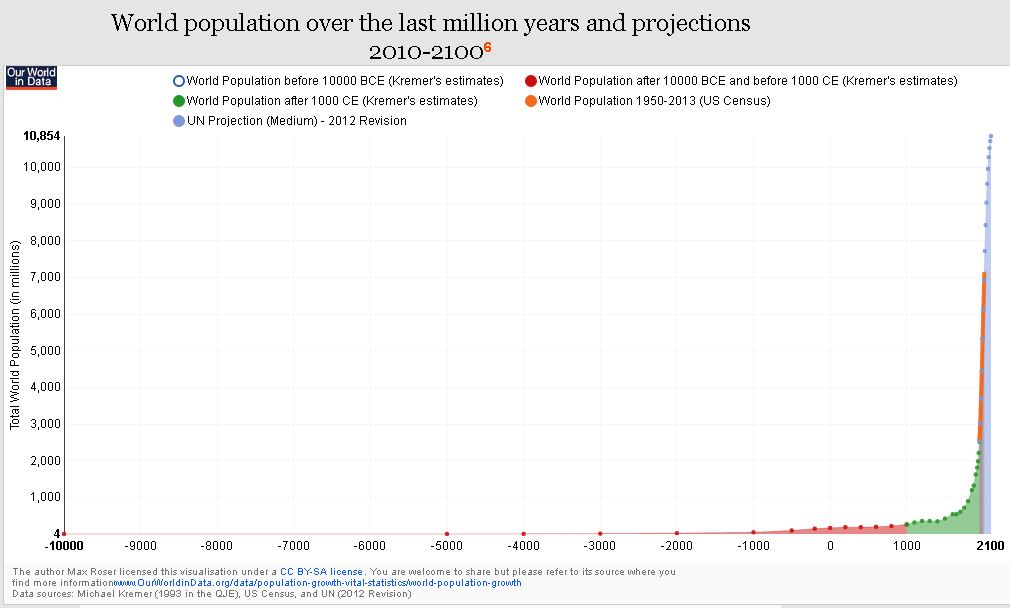

World Population

Unsurprisingly, total world population numbers have increased dramatically as well. If Big Pharma, the Great and Terrible MonSatan, the Shilluminati Reptilian Shadow Government, or any other shadowy forces are indeed engaged in some elaborate conspiracy to harm everybody for personal gain, their execution has left much to be desired insofar as any and all outward appearances are concerned.

Of course these facts all raise additional questions and other issues. What are the most influential causes of the life expectancy increases we’ve seen, and just how much greater could human life expectancy, max longevity, and global population conceivably get?

Transhumanism and Life Extension

If you’re familiar with the transhumanism and life extension movements, you may be aware that these are some of the important questions faced by proponents of indefinite life extension. They are also the topics of some of the common criticisms of the life extension enterprise.

See, the life extension movement has a concept called “longevity escape velocity,” which describes a hypothetical situation in which the rate at which life expectancy increases actually outpaces time itself. However, despite steadily increasing life expectancy numbers, changes in maximum longevity over time have been far less dramatic. Jeanne Calment, who died in 1997 at the age of 122, still holds the official world record as the oldest verified person on record, and although several others have made it into their one hundred and teens in the subsequent years, none have verifiably broken the 120 barrier, whereas life expectancy numbers have increased by at least a few years in nearly every country between 1995 and 2015.

Without also increasing longevity numbers, life expectancy could only keep increasing for so long until the mean life expectancy would approach max longevity as a narrow bell curve with a small variance and standard deviation. The biological limits of the human life span are not well known or well understood at this point, and there is much debate and speculation as to how long a person could potentially live. Anyone interested in learning more about the challenges faced by life extension researchers (insufficient funding not withstanding) can check out the works of Aubrey de Grey and Alex Zhavoronkov for more information.

Overpopulation

The issues of life extension and population growth also raise the issue of Malthusian catastrophe. Biotechnology can help with agricultural efficiency and productivity to a point, but it’s unclear the extent to which our technology can continue to keep pace with a growing population, and that’s only touching on the food aspect of resource allocation. Debates on the prospect of potential overpopulation run the gamut from extreme pessimism to optimism insofar as predictions as to whether technological solutions will win in the end. I can’t claim to know, in large part because I don’t view current trends as a viable basis for reliable projections that far into the future, but I tend to lean towards the idea that technological innovation will likely surprise us for the better. Steven Novella has laid out a couple of the more salient pro and con arguments here.

As far as what has caused the steadily increasing life expectancy over the last 150 years or so, there doesn’t appear to be a solid scientific consensus on the specific minutia, but it is probably safe to say that scientific knowledge and technology have been important contributors. In the concluding synthesis section at the end of their paper, “The Determinants of Mortality,” Cutler et al argue that improved housing, sanitation, and medical technology, the germ theory of disease, vaccines, advanced pharmaceuticals, and improved nutrition have likely all contributed to varying degrees.

Conclusion

Life expectancy has increased steadily for the last 150 years or so, and it cannot be attributed solely to the reduction in child mortality. This may not conclusively rule out the claim that dark forces are conspiring to wipe us out with GMOs, vaccines, chemtrails and water fluoridation; but if they are, it shows that they’re failing spectacularly at that task.